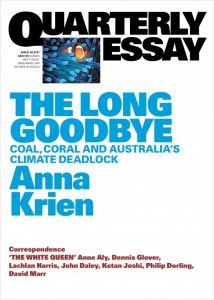

Review: Anna Krien’s ‘The Long Goodbye’

Coral reefs are extraordinarily beautiful, diverse, complex ecosystems. It is their diversity and complexity, in no small part, which gives them their beauty – colour and movement, ever changing, ever shifting, something to take your breath away everywhere you turn.

Coral reefs are extraordinarily beautiful, diverse, complex ecosystems. It is their diversity and complexity, in no small part, which gives them their beauty – colour and movement, ever changing, ever shifting, something to take your breath away everywhere you turn.

It is, of course, that diversity, and the complexity of interplays and connection, which gives them their resilience, as well as their beauty. And it is only through understanding the myriad ways in which we humans are changing our world, as Anna Krien helps us do, that we can come to grips with our destruction of that resilience and beauty.

Too often, commentary on climate change follows the simplistic path of linear thinking (if x, then y), of horse-race politics (x outplayed y), or of duelling dualisms (either x or y is the cause, and we can ignore the other). How many times have we witnessed bickering about whether climate change or run off or crown of thorns starfish were the cause of the Great Barrier Reef’s woes, when it is clearly the interplay between all of these and more? How often have we been assured that, if we click here, email this politician, shift our funds there, we can “save the reef”? How many times have we voted in elections between parties assuring us they will protect the reef better than their opponents?

In The Long Goodbye: Coal, Coral and Australia’s Climate Deadlock Anna Krien has woven a masterful web around all of this, painting a wonderful, multi-dimensional picture of the state of the Great Barrier Reef and what has led us here. Her critique takes in everything from the singular dominance of the fossil fuel sector in our political discourse to roadside advertising for fertiliser in Far North Queensland, from the systemic dispossession and deliberate division of Indigenous communities to the global politics of climate change negotiations and international trade, from human stories of individual heartbreak and loss to the overarching story of a planet in dire crisis.

Krien places the reef’s woes firmly into the heart of the failure of our economic and political system. Our economics cannot value it, because it is impossible to value the invaluable. Our politics cannot make the necessary systemic changes, because it embodies the system which continues to drive the damage.

It is here where Krien’s essay presents its crucial insight: the fundamental failure of a politics which presents itself as “non-ideological”, “practical”, a “sensible centre”, while in fact ideologically implementing the demands of rent-seeking corporations.

“Turnbull and Shorten may say there is no ideology in their politics, but this can leave one wondering, what remains? A desire for power, a painted portrait in parliament, an entry in the history books? But for what? Just for the sake of it?”

Although Krien doesn’t say this explicitly, there is something deeply nihilist in a politics which is willing to plunder and destroy while claiming no ideology at all.

What are we to do in the face of that?

It is this crucial insight, however, which leads to my one criticism of this excellent essay.

It is too thoroughly permeated with a sense of defeat. There is a tangible deep sadness throughout, from the title, “The Long Goodbye”, to the final sentence, “The reef isn’t dead. But it can’t breathe”. You can taste the tears Krien shed while writing it. Even the stories of those fighting, such as Andrew Morrell and Bruce Currie, are tinged with sadness and defeat.

This is completely understandable. Appropriate, even. All of us working in the field, and many on the outskirts of it, feel this sense. We mourn the Reef, as we must, and as we do so many other precious parts of our world we are destroying.

But there is another side to the story, one that is darkly reflected in Krien’s closing words: “It can’t breathe”.

“I can’t breathe”, Eric Garner’s final words as the life was crushed out of him by a New York policeman, have become a rallying cry of resistance in the Black Lives Matter movement.

The Great Barrier Reef, as Krien so eloquently tells us, can’t breathe. It is very likely too late to save it, as it is far too late to save Eric Garner. But it must not be the end. We can and must resist, mobilise, change. And this is already happening, in so many ways. And it is winning. Too slowly, of course, but very noticeably.

It is highly unlikely, for example, that the Adani Carmichael mine will be built. The strategy of delaying it, through protest, divestment, direct action, legal challenges and more, until it is clearly economically unviable has worked. Adani’s continued commitment to the project seems like so much theatre for the viewing pleasure of overseas investors. The campaign to prevent it must, of course, continue as well to absolutely lock this in. But the global peak in coal use has been and gone, renewable energy has won the race, and it’s all over bar the shouting.

As reported recently in Renew Economy, North Queensland is now set to be a huge solar energy export zone, with plans underway for 4 gigawatts of solar power to be built, powering mines and industry as well as homes, schools and hospitals, and exporting to the south of the state.

But the fact that this job creation, industrial and pro-environmental bonanza is ignored while a handful of jobs in an environmentally and socially destructive 19th century industry continue to be talked up, shows quite how much of a “transformation of the mind”, as Krien puts it, we still need.

Just as the Great Barrier Reef is a complex, diverse ecosystem, and the causes of its dire state are complex and interwoven, the solutions too must be complex and diverse. We must enable Indigenous Australians to seek their own, sustainable future, with a deep understanding of climate justice. We must create opportunities for people struggling in a post-industrial landscape to find meaningful lives, whether it be through job creation, education, or localised trials of Universal Basic Income. We must ensure that scientific advice is respected, instead of buried under the demands of rent-seekers. We must challenge roadside advertising, which curates too much of the story of our world, telling us we are consumers rather than citizens, making us feel we need products such as particular fertiliser, despite knowing the damage it causes, despite government-sponsored programs to reduce its use.

And we must break out of a politics which assumes that nothing can change, that a corporate-dominated status quo is “non-ideological”.

Perhaps then “The Long Goodbye” might not be so final.

comments

Add comment